Welcome to Carbongrad

In its least ideological form, Sovpunk comes to (still) life in Evgeny Zubkov's series of online artwork known collectively as "Carbongrad 1999" (and has also been rebranded as "Russia 2077"). Steeped in the aesthetic of Blade Runner-era cyberpunk, Carbongrad 1999 consists of clever variations on a single conceit: the seamless integration of Russian and Soviet everyday imagery into a gritty, urban high-tech landscape.

Visitors to his VKontakte and Instagram accounts are treated to photorealistic images of an old Russian women in customary drab garb (ill-fitting sweater, gray skirt, flower-patterned headscarf) feeding flying robot drones as if they were birds, a middle-aged man in knee-high rubber boots carrying rusty buckets of water in each of his arms (including the two robotic ones sprouting form his back), and an orange-jacketed worker using a hose from his clunky water truck to clean off the graffiti from a giant, hovering mechanical sphere that looks like a mini-Death Star. Perhaps the most iconic of all the "Carbongrad" images is a bald, track-suited cyborg carrying a baseball bat studded with bolts and decorated with two stickers, one a robotic version of the woman holding a finger to her lips from the famous World War II "Don't Blab!" poster, the other apparently the eponymous heroine from "The Girl from the Future," both partially obscuring a warning familiar to anyone who has ever stood in front of a Russian subway door: "No leaning!"

Zubkov's combination of the cybernetic and quotidian is not, in itself, new; the artist himself freely acknowledges his debt to Simon Stalenhag, the Swedish artist known for his haunting paintings of retrofuturist machines set against the bucolic backdrop of his native countryside.[1] Zubkov shares more than just Stalenhag's aesthetic; equally important is how they both downplay the strangeness of their subject matter. Each artist engages in what Olga Meerson has called "re-familiarization" or "non-estrangement" (neostranenie), the process of describing something new and odd as if we were expected already to know all about it.

Zubkov's art casually asserts an important point about Russia's future; namely, that Russia has one. True, Zubkov describes his imaginary world as an "alternate present," but what makes it alternate are the futuristic elements that share space with familiar Russian realia. This combination of Russia and (retro)futurism might well be understood by analogy to the largely anglophone movement known as Afrofuturism. At its most basic, Afrofuturism pushes against the overwhelming whiteness of most twentieth-century science fiction simply by depicting a future that, at minimum, has Black people in it, and, more boldly, moves Blackness from the background to prominence.

It is this minimum that Zubkov achieves in Carbongrad 1999. Unlike the more militant Sovpunk to be discussed in a later post, Zubkov's deployment of Russian and Soviet signifiers is unaccompanied by patriotic bluster. He achieves this understated "Russofuturism" by avoiding the most obvious signs of Russian statehood and national pride, creating an imaginary geography that is maximally distant from the sites of empire. If we had to place Carbongrad somewhere on the maps of Russia, it would be deep in the North. Russia outside the capitals can be romanticized, and certainly has been by blood-and-soil traditionalists, but the conservatives' chosen setting is usually the countryside. Zubkov's world is both provincial and urban, located firmly within the modern world yet far from the traditional loci of significance in Russia. [2]

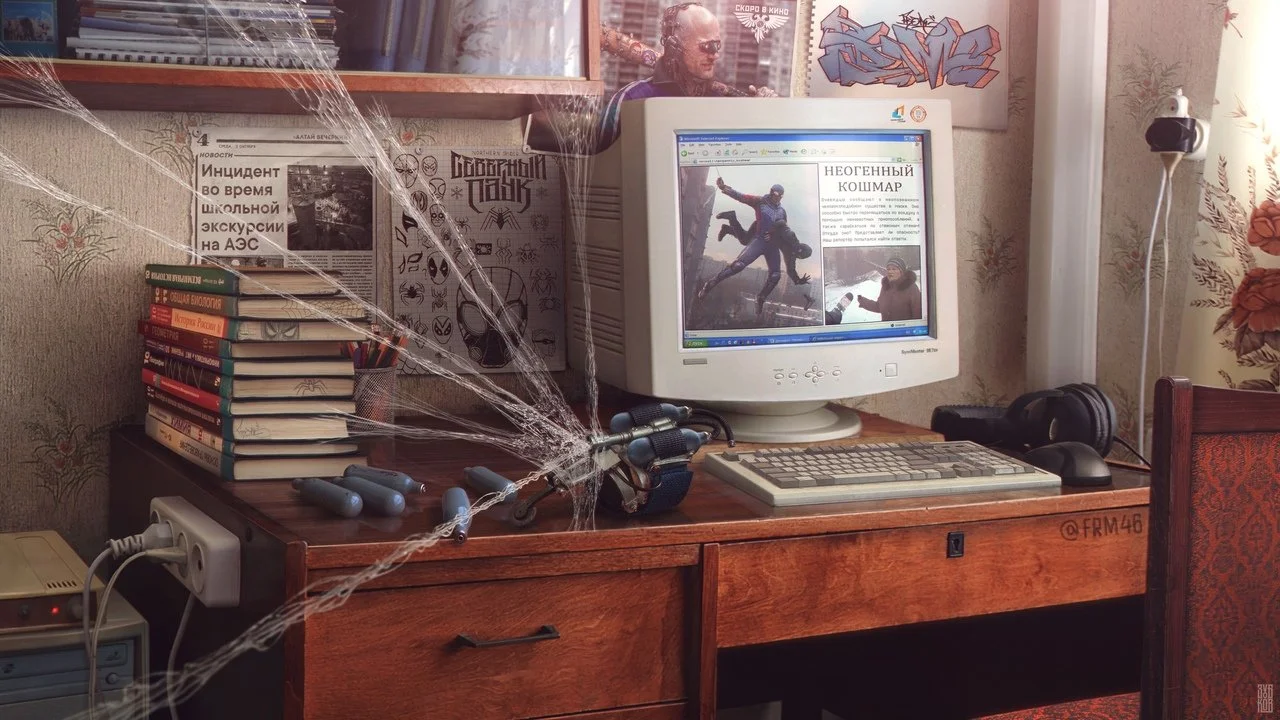

Zubkov's imaginary Russia is a palimpsest in which the past, present, and future overlie each other. Unlike DSDS's 2045 video, it seems indifferent to questions of Russia's destiny and unwilling to police the boundaries of the Russian cultural imagination. Zubkov paints a set of worlds that can comfortably domesticate any external influence without making a fuss, even Western pop action heroes. In the "Northern Spider" series, Spider-Man is reimagined as a resident of an unnamed Russian provincial city. His costume retains the familiar red and black color scheme, but appears to be made of more realistic components, cobbled together from clothing that might conceivably be available to an ordinary person. There is no need to give this version of Spider-Man any particularly Russian stylistic attributes (no two-headed eagles or Russian flags); he is Russified simply by his inclusion in an environment that is clearly far from Queens. In one picture he shoots webs at a monstrous mecha-truck as a babushka looks on, a grocery bag in each hand. Another shows what looks to be the Russian Peter Parker's bedroom, complete with a cobweb made out of his webbing, a turn-of-the-century computer showing a newspaper story about his first appearance that shows the Northern spider in an homage to the iconic cover of the first Spider-Man story , and a newspaper clipping suggesting that the Northern Spider got his powers during a school trip to a nuclear power plant.

Zubkov works the same sort of magic in his "Russian Turtles" picture, which announces itself (in English) as "An alternative universe in which 4 mutated turtles were born in Russia in the mad 90s." Leonardo now carries an AK-47, Donatello sports a sputnik tattoo, Michelangelo is holding a shawarma in a pose suggesting either a weapon or his next meal, and all of them are wearing sneakers and ski masks. Instead of their customary sewer, the Turtles seem to have made their home base in a junk yard. Situating the Turtles in the Russian 1990s is a clever choice, and not just because most of the original cartoon aired in that decade. The original Turtles' scrappy, DIY aesthetic, along with their status as muscle-bound brawlers, makes it easy to imagine them in the messy world of Russian gangsters and general instability.

The artist's casual incorporation of futuretech and Russian reality, not to mention foreign popular culture, is a relaxed, optimistic alternative to both alternate history and future history. For Russia to persist in the future, or for the future to make its way into present-day Russia, not a great deal has to change. "Russianness" (as depicted in the everyday realia) is neither extolled nor condemned; the persistence of visibly Russian tropes in an imagine future could be seen as a gesture towards a cyclical, determinist model of the nation's history, i.e, that Russia will not and cannot ever change. But the lived-in feeling of Zubkov's work points in a different direction: Russia can make its way into the future while still remaining visibly Russian. There is nothing to fear from new technology, just as is there is nothing to fear from the influx of Western animated turtles and web-slinging teens. Russia can absorb the new without losing itself.

Notes

[1] He is probably best known for Tales from the Loop, a narrative art book that inspired a science fiction series on Amazon Prime in 2020.

[2] Here I am obviously influenced by Anne Lounsbery's brilliant study, Life Is Elsewhere: Symbolic Geography in the Russian Provinces, 1800-1917.