Unwatchable Watchmen

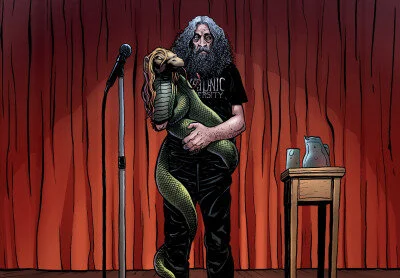

Alan Moore is not a one-trick pony. In addition to writing dozens of groundbreaking comics/graphic novels, he has also published two prose novels, performed live multimedia dramas, drawn his own comics when he was starting out, and declared himself a ceremonial magician who worships a snake god.

NO JUDGMENT

Movies, however, are his kryptonite.

This is not Moore’s fault: he does not write for film, nor does he direct. But he is the successful creator of a great deal of intellectual property that Hollywood has been only too happy to develop (or exploit, depending on your point of view). Moore refuses to watch the film adaptations of his books, and, starting with Watchmen, will not even accept credit or payment for the resulting work (the Watchmen film is based on the graphic novel “co-created by Dave Gibbons"). His preference would be for his work to be left alone, but he falls back on the consolation that the original comics are still there, on the printed page, undisturbed by their cinematic counterparts.

Five films have been made out of his comics work: From Hell (2001), The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (2003), V for Vendetta (2005), Watchmen (2009), and an animated version of The Killing Joke (2016). In addition, an episode of the Justice League Unlimited cartoon was adapted from his comic “For the Man Who Has Everything” (2004), and is my personal choice for most successful translation of Moore from page to screen.

The live-action versions of Alan Moore’s comics have ranged from aesthetic misfire (From Hell) to outright bastardization (The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen). The Wachowskis’ V for Vendetta does a passable job of bringing the graphic novel's themes and characters to the screen, but crashes and burns at the end, transforming the Guy Fawkes mask worn by the protagonist from an emblem of individual, yet anonymous anarchic resistance to a collective icon worn by everyone in a crowd. The cinematic V for Vendetta starts out raging against the machine, but ends up looking like a Dr. Pepper commercial (“I’ve a vendetta, he’s got a vendetta, wouldn’t you like to have a vendetta, too?”).

LOOK! IT’S A BUNCH OF INDIVIDUALS!

Watchmen’s critical and commercial success could not have escaped the notice of Hollywood, For a time, Terry Gilliam was attached to the project, which gave some cause for optimism. Not because Gilliam’s aesthetic was similar to Moore’s, but simply because he had a unique authorial vision that might have helped him rise to the challenge. After years in development hell (including the now prophetic suggestion that the book would be better adapted as an HBO miniseries than as a feature film), it finally ended up in the hands of Zack Snyder. For years, critics had suggested that Watchmen might be unfilmable, and it was now up to Snyder to prove them right.

Zack Snyder’s Watchmen is a strange sort of failure. Unlike, say, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, which drained all the cleverness out of the story while shoehorning Tom Sawyer into the plot in a strange attempt to engage American audiences, Watchmen suffers as much from fidelity to the original as it does to deviation from the source.

No one could every accuse Snyder of being an outsider to the culture of comics. Watchmen is the second of eight comics-based films associated with Snyder’s name.

Most of them, however, are terrible.

Snyder has clearly given superhero comics a careful study, but he has come to all the wrong conclusions. Moore once lamented that Watchmen had influenced subsequent comics in a way he never intended:

It was the 1980s, we'd got this insane right-wing voter fear running the country, and I was in a bad mood, politically and socially and in most other ways. So that tended to reflect in my work. But it was a genuine bad mood, and it was mine. I tend to think that I've seen a lot of things over the past 15 years that have been a bizarre echo of somebody else's bad mood. It's not even their bad mood, it's mine, but they're still working out the ramifications of me being a bit grumpy 15 years ago.

Watchmen and Frank Miller’s Batman: The Dark Knight Returns inaugurated a decades-long superhero trend: “grim and gritty” or “grim dark” stories, replete with ultraviolence, torture, sexual assault, and cheap cynicism. The effect on DC Comics (Watchmen’s permanent home) has been particularly pronounced. For years, Marvel had the reputation of being more “realistic” than DC, while DC was relatively lighthearted and lightweight.

Now the tables have turned. Marvel manages to tell a broad spectrum of stories in a variety of emotional tones, while DC has repeatedly doubled-down on dark violence, even after declarations that the age of darkness is over. In the twenty-first century, some of DC’s biggest stories have featured the rape and murder of an obscure but beloved whimsical supporting character (Sue Dibney in Identity Crisis), arms torn off not one but two superheroes (Risk and Roy Harper/Arsenal from the (Teen) Titans), and a group of rage-filled Red Lanterns who continuously vomit blood. [1]

HEY, KIDS! COMICS!

Zack Snyder is in perfect alignment with this particular trend, mistaking blood and gore for depth, confusing melodramatic pain and suffering with emotional growth. In Batman v. Superman: Dawn of Justice, by the time the two heroes are done punching each other and bonding over the unremarkable fact that both of their mothers were named Martha, audiences could be excused for looking back fondly at the days of “Biff!”, “Bam!” And “Pow!”

In the graphic novel, when Hooded Justice stops the Comedian from raping Sally Jupiter, he is justifiably enraged, first punching the Comedian in the face and then kneeing him in the gut. “You sick little bastard, I”m going to break your neck…”he shouts, to which the Comedian responds: “This is what you like, huh? This is what gets you hot…” Hooded Justice stops cold, and the Comedian tells him: “I got your number, see?”

The Comedian implicitly suggests that his own violent sexual assault is on a continuum with Hooded Justice’s internalized sexualization of violence, and the reader who has been viewing these two pages also cannot escape complicity. But it also seems that, if the Comedian’s has got anyone’s “number,” it’s Zack Snyder’s.

Snyder’s trademark approach to filming brutal violence is a long, almost loving slow-motion take, such as when we see Hollis Mason’s teeth flying out as he is being beaten to death. Slow-motion has its use in action scenes; it allows the viewer to see just what is happening in an otherwise rapid sequence of events. But that’s not what is at work in Synder’s films, particularly Watchmen. Snyder is making sure that the viewer gets the maximum voyeuristic thrill from every kick, punch, and dismemberment.

I’D BEEN WONDERING IF HE HAD AN ELBOW BONE. THANKS FOR CLEARING THAT UP, ZACK!

One of the most common criticisms made by devotees of the graphic novel has to do with the film’s ending; Snyder replaces Adrian Veidt’s alien squid monster with a duplicate of Dr. Manhattan. [2] While I have already made the case for the thematic important of Veidt’s master plan in the Watchmen comic, I still think that the ending is the least of Snyder’s problems. Instead, Snyder’s film is weak in three particular categories: bodies, humor, and dialogue.

Before the movie was ever made, fans wondered how a film would deal with Dr. Manhattan’s perpetual nudity, or, to put it more bluntly, the “giant glowing blue wang” problem. American cinema is famously prudish about penises, a fact that was hilariously satirized in the 2007 Simpsons Movie, when a naked Bart skateboards through town, with a series of well-placed obstacles preventing us from seeing his penis, and Chief Wiggum’s cry of “Stop in the name of American squeamishness!”

THE MORALITY OF MY ACTIONS ESCAPES ME

To his credit, Snyder did not shy away from penis problem, much to the amused delight of a wide array of reviewers. Dr. Manhattan lets it all hang out. This makes some sense, because Snyder’s film is committed to a superhero aesthetic ideal that the graphic novel does its best to undermine: the ideal of the perfect physique.

In the comic, Laurie’s choice of Dan over Jon is all the more poignant (and all the more marked) because, where Dr. Manhattan’s body is so close to the male ideal that the back matter actually draws him as da Vinci’s Vetruvian Man, Dan is middle-aged guy who has let himself go. Jon’s radiant rod is no problem, but Dan’s pot belly cannot be put on screen.

This may seem like a minor detail, but it is part of a larger package (sorry). In the film, Dan does nothing to deviate from the superhero stereotype. When he beats up one of the knot tops after Hollis’ death, the comic shows it to be out of character, while the film just uses it as an excuse for more slow-mo torture porn. And when Dan learns of Rorshach’s death, Snyder turns him into a complete cliché: after screaming “Noooo!,” he lunches at Adrian and punches him repeatedly.

The only thing worse than Dan’s violent episodes is his sex scene. The comic gives us a sequence of wordless panels, set to Billie Holliday. The film chooses “Hallelujah,” a beautiful song that had already been irreversibly overexposed. Does anyone really want to be thinking about “Shrek” during a sex scene? And then there’s the bumping, grinding and groaning that sums up Snyder’s aesthetic perfectly.

DON’T WORRY, LAURIE. THE MOVIE’S ALMOST OVER

Part of the problem is how desperately Snyder wants to show us that this is serious business. So serious that the many moments of humor in the comic are either ignored or bulldozed over. Dan and Laurie’s reminiscences of the masochistic villain whom Rorschach dropped down and elevator shaft fall flat, while their conversation during Rorschach’s murderous bathroom break (when he murders Big Figure), a moment of mundane hilarity in the comic, is replaced by Laurie’s expressions of frustration.

In a movie trying so desperately to be faithful to the original, the changes Snyder makes in dialogue are frustrating. In the comic, when an imprisoned Rorschach is taunted “What do you got?” by a man on the other side of the prison bars, Rorschach grabs his hands and ties them together on his side of the bars, saying “Your hands. My perspective.” In the film: “Your hands. My pleasure.” It’s not just worse; it doesn’t even make sense.

Finally, there is an aspect of the dialogue that may well not have been Snyder’s fault. Moore’s dialogue is carefully written, even poetic. On the page, it also looks natural. But it is not naturalistic. Douglas Wolk notes that, when Moore’s characters are saying something important, they tend to lapse into an iambic rhythm. A great director can pull that off (see under: Deadwood), but it’s no easy thing. More to the point, dialogue that sounds brilliant on the page might sound less inspired when spoken aloud.

That, I think, is the heart of the problem. Watchmen was not just a comic book; it was a proud comic book, an artistic manifesto exemplifying what makes comics special as a medium. Nearly all the clever structural devices, particularly the constant counterpoint between the voiceover narrative and the action on the page, not to mention the interpolation of Tales of the Black Freighter, work only in their original environment.

Anyone adapting Watchmen should know that the Doomsday Clock tolls for them.

Notes

[1] To be fair, though, as part of Marvel’s 2006-2007 Civil War crossover event, Paul Jenkins transformed Speedball, a stupidly whimsical character with bouncing powers and a name that he unfortunately shared with a street drug, into a pain-powered, angsty masochist who harnessed his abilities while wearing a leather gimp-suit studded with inward-facing spikes. So there is that.

[2] To get a bit of perspective on how the superhero world looks to outsiders, I recommend hardcore comics fans read this sentence aloud.

Comments (1)

Anders Davenport 6 months ago · 0 Likes

“In the twenty-first century, some of DC’s biggest stories have featured the rape and murder of an obscure but beloved whimsical supporting character (Sue Dibney in Identity Crisis), arms torn off not one but two superheroes (Risk and Roy Harper/Arsenal from the (Teen) Titans), and a group of rage-filled Red Lanterns who continuously vomit blood. [1] Zack Snyder is in perfect alignment with this particular trend, mistaking blood and gore for depth, confusing melodramatic pain and suffering with emotional growth.”

You’ve perfectly summed up why the Watchmen movie gets everything wrong about the book even though it recreates so many of the visuals.

“The film chooses “Hallelujah,” a beautiful song that had already been irreversibly overexposed. Does anyone really want to be thinking about “Shrek” during a sex scene?”

Actually, that sentence sums up the movie even better!