Self: Sufficient? Omega the Unknown’s Mind/Body Problem

The typical Gerber hero suffers from detachment—in the case of the Defenders' various heads and brains removed from bodies, literally so. Small wonder that Gerber created the Headmen, since most of his characters tend to live in their own heads. Again and again, the solution for the plight of the reticent intellectual is connection and empathy. In the figure of the Man-Thing, Gerber had a mindless creature based entirely on emotion, who played a decisive role at key moments in the story’s but otherwise functioned as the drama’s silent chorus. In Omega the Unknown, Gerber and his writing partner Mary Skrenes co-created the Man-Thing’s counterpoint: a thirteen-year-old boy whose superior intellect is complicated by a near-incapacity to connect with his own emotions or those of others.

Omega the Unknown ran for just 10 issues in 1976 and 1977 before its abrupt cancellation, its mysteries wrapped up two years later by Steve Grant in a Defenders storyline that even its writer found unsatisfying. In fact, despite the character’s obscurity, more comics featuring Omega were scripted by other writers than by Gerber and Skrenes. Issues 7 and 8 were credited to Scott Edelman and Roger Stern, respectively; their single-issue assignments were probably the result of Gerber’s notorious lateness. The character was subsequently revived and rebooted by Jonathan Lethem and Farel Dalrymple in a ten-issue limited series in 2007, the result of Lethem’s childhood fascination with the original comic (Lethem even included references to Omega in his 2003 novel The Fortress of Solitude).

Omega the Unknown was an unusual comic, even by the standards of Seventies Marvel in general and Gerber in particular. Superficially, it is the most prominent example of Gerber’s Superman fixation; after all, the title character wears a red-and-blue costume, a cape, and a headband that would not have been all that out of place in the trendiest spots on Krypton. A rocket carries him from his doomed planet to ours. Unlike Superman, he arrives as an adult, but he shares the comic with a child, James-Michael Starling, orphaned, like Superman, in the very first issue. The two characters also share a physical resemblance and a mysterious bond, suggesting a variation on not just Superman, but the original Captain Marvel (a young boy transformed into a superpower adult by saying the magic word “Shazam:”). Yet Omega and James-Michael invert the dual identity tropes of their predecessors. The biggest challenge to Superman’s maintenance of his secret identity was that he and Clark Kent could not be seen in the same place at the same time (the same was true for Captain Marvel, but it never became much of a plot point). James-Michael and Omega certainly do co-exist. The problem is that we can never quite be sure why.

The man eventually referred to as Omega is apparently the last survivor of a planet overrun by robots; he arrives on Earth (in New York, of course) in the very first issue, and is nearly killed by one of the robots who follow him, Omega, who does not speak a single word in the first three issues (and only one in the fourth), tries to blend in, but is repeatedly drawn into senseless battles: with the Hulk (issue 2), the villainous Electro (issue 3), and the local brujo known as “El Gato” (issues 4-5). Along the way he is accidentally shot, then subsequently befriended, by an old man (“Gramps”) whose nonstop chatter makes up for Omega’s studied silence. Omega has no clear motives beyond his own survival and the protection of young James-Michael.

James-Michael had spent his entire life homeschooled by his parents in a futuristic house in the mountains somewhere in Pennsylvania. When the series begins, his parents are driving him to New York, where he will attend school for the first time (his parents insist that it will be good for him; James-Michael says that other children “bore” him). A car accident kills his parents, but not before James-Michael has one last conversations with his mother, whose head was ripped from her body, revealing that she was a robot. His mother’s head warns James-Michael not to listen to “the voices,” and then melts away. James-Michael has a brief psychotic break, only to awaken in a charity hospital in Hell’s Kitchen. When a robot breaks into the hospital to attack him, Omega is not far behind, and James-Michael surprises himself by knocking out the robot with energy blasts that leave omega-shaped stigmata on his palms (Omega himself displayed the same powers a few pages earlier).

James-Michael is taken in by Ruth Hart, a nurse at the hospital (and former Man-Thing supporting cast member), along with her roommate, Amber, to share their tiny Hell’s Kitchen apartment.[1]. The Hell’s Kitchen setting is integral to Omega, since nearly all of James-Michael’s troubles, as well as his education in ordinary humanity, are the result of his confrontation with non-stop human misery and cruelty. He makes two friends at school: a tomboy named Diane, whose sarcasm and brusk manner make her a pubescent analog to the streetwise Amber, who clearly intrigues the boy; and John Nedly, a fat outcast and would-be writer. Nedly is horrifically beaten by bullies, and issue 10 starts with his funeral.

If this doesn’t sound like much in the way of plot, then my summary is successful. In part because the series was so quickly cut short, in part because of fill-ins and deadline problems, and in part because of the Omega the Unknown’s awkward fit in a mainstream superhero universe, very little progress is made in solving the three enigmas announced in the introductory text on the splash page of every issue:

ENIGMA THE FIRST: the lone survivor of an alien world, a nameless man of somber, impassive visage, garbed utterly inappropriately in garish blue-and-red. ENIGMA THE SECOND: James-Michael Starling, age twelve raised in near-isolation by parents who (he discovered on the day they "died") were robots. ENIGMA THE THIRD: the link between the man and the boy, penetrating to the depths of the mind and body, causing each to question his very reality of self.

These introductory captions were standard at Marvel at the time, but Omega’s is appropriately unusual. It sets up the two main characters, raises the question of their character, and then gives absolutely no indication about the actual plot. Even in what should have been a boilerplate blurb, theme trumps plot, and that theme announces itself in italics in the very last word: self.

Omega the Unknown checks all the standard Gerber boxes: interrogating the genre (Omega doesn’t understand the fights he keeps getting in), social commentary (everything about Hell’s Kitchen), and existential critique. Though the social commentary is the most obvious, it is the existential critique that connects the book's disparate elements (first and foremost, Omega and James-Michael themselves). The alienation of Gerber’s archetypal protagonist, Howard the Duck, is a function of his idiosyncratic, uncompromising selfhood: he has a perspective on the world, and he will not yield. On the other end of the spectrum, Man-Thing is literally self-less, serving as a catalyst for the self-exploration of those around him. Omega and James-Michael occupy a strong middle ground: unlike Man-Thing, they can, and do think, but, unlike Howard, they start the book with a strangely rudimentary sense of self.

Omega, as we have seen, spends most of the comic in silence, but the sequences that focus on him are accompanied by a large number of narrative captions, mostly in the third-person limited. We’ve seen something like this technique before, when Marv Wolfman would dedicate a series of panels to conveying the consciousness of Dracula’s victims immediately before the vampire’s attack. Wolfman leaves the reader with a strong sense of who the victim was. The comparable captions in Omega the Unknown leave Omega still…unknown.

Lethem, and, following him, Jose Alaniz, refer to these sequences as “Omega monologues” or “soliloquies,” but they are actually neither. Using “Omega” as the modifier to these series of captions suggests that, whatever term we might use to describe them, their subject is Omega himself. On the surface, we could be reading free indirect discourse, but Alaniz correctly points out that in one of the last such “soliloquies” in Issue 10, the “off-kilter narration” seems to “blithely go off on its own,” particularly when the narrator exclaims ”You cad!” as Omega is thrown into a ravine. Alaniz connects it to the idea of “autistic presence,” and notes that Lethem observed that Gerber seemed to be writing his way “out of the human race.”

I am not entirely comfortable with the attempts to place Omega the Unknown within the category of autism, except perhaps along the lines of the “autistic poetics” described by Julia Miele Rodas. Alaniz’s connection of James-Michael to Bruno Bettlehiem’s “Joey, the Mechanical Boy” is useful less because of considerations of actual autism than due to Bettleheim’s thoroughgoing wrongness about autism. James-Michael and Omega arguably embody a neurodiverse subjectivity, but only to the extent that any non-normative consciousness fits this designation.

The “Omega monologues” are crucial because of the way in which they fail to be monologues. They point to a gray area between phenomenology and ontology, not entirely about the characters experience of consciousness as about the underdeveloped subjectivity that could be experiencing consciousness. It is fitting that James-Michael and Omega are linked and share an obvious resemblance, because each of them, on his own, fails to be an entire self. The James-Michael/Omega doubling emphasizes the incomplete, fragmentary nature of their selfhood.

At the same time, neither James-Michael nor Omega are static characters; their selves may be incomplete, but the story of Omega the Unknown is that of their coming-into-selfhood. This is not exactly a Bildunsgroman; it is something stranger.

Stranger, but not unprecedented. On occasion, novelists have created protagonists who need a great deal of time to mature into a full sense of their own subjectivity. Gregory Maguire’s Wicked Years novels, for instance, start with a protagonist (the Wicked Witch of the West), whose sense of self and perspective on the world around her is so strong that all the protagonists of the subsequent three novels not only pale in comparison, but take decades to develop a sense of agency and a point of view (Liir in the second book, the Lion in the third, and Rain in the fourth). They are all observers of their own lives rather than active participants.

James-Michael is reminiscent of Sasha Dvanov, the hero of Andrei Platonov’s 1929 novel Chevengur. Dvanov, too, lives his life at a distance. The narrator tells us that somewhere inside his head lives a watchmen: “He lived parallel to Dvanov, but wasn’t Dvanov.

“He existed somewhat like a man’s dead brother; everything human seemed to be at hand, but something tiny and vital was lacking. Man never remembers him, but always trusts him, just as when a tenant laves his house and his wife within, he is never jealous of her and the doorman.

"This is the eunuch of man’s soul.”

Valery Podoroga concludes that Chevengur is a story told by a “castrated consciousness.” If we connect this to Omega the Unknown, one might imagine the dual protagonists could be divided into “conscious, emotions, and human” on the one hand and the “trusted dead brother” on the other. But the story with Omega is even stranger than that. Both Omega and James-Michael start out as closer to the “watchmen” figure than to the “normal” consciousness. These are not two halves that make a whole: these are two halves that are slowing growing their missing pieces.

Consider the first “Omega monologue” from issue 1, which sets up a pattern that will recur throughout the series.

“The mind searches furiously for a key to it all: what is it? What went wrong? Why? How?

“The body, meanwhile…

“…does what it must…

…to survive!"

Though Omega will be referred to as “he” for the rest of the series, the very second page of his first appearance establishes him as something other than a simple unitary self. His mind and body function separately, if at times in parallel. This could explain some of the strangeness of the monologues, in that they always seem to hover around Omega rather than represent his coherent point of view. Like the narrator of Howard the Duck 11 who takes over the running commentary when everyone is briefly unconscious, the “Omega monologues” narrate on behalf of a consciousness that does not quite exist.

The various parts that make up Omega proliferate on those first pages, for, in addition to mind and body, he is also the conduit for a mysterious power:

“For the chaos, the tumult raging all about this last of his superior breed…

“…could only bye the product…

“… of the pain..

“…and the passion…

“…and the fire…

“To which he alone remains heir.

“The energy—the creative force—could be disciplined only so strictly, held meeting in check only so long, before it burst forth…

“…ravaging, mindless, uncontrollable.”

First we should not that tumult is raging “all about’ him, rather than something he is directly experiencing, and yet it expresses itself in an outpouring of energy issued directly from his palms. This “creative force” is the third element of Omega’s not-quite-self, the only one that is directly connected to emotion. Not just emotion, but passion: the build up, the “bursting forth,” have an element of the orgasmic about them, Small wonder that the narrator’s conclusion at this point is that “An organism ceases to live when it ceases to grow.” Not only is Omega on a path that will lead him to growth, but this scene immediately cuts to the pubescent James-Michael as he wakes up screaming from a nightmare. This “creative force” is the libidinal element otherwise absent from the castrated consciousness. When James-Michael wakes up from this nightmare, it is of course, nothing like sexual release, but his repetition of Omega’s fiery ejaculation on the issue’s last page suggest that something libidinal is finally awakening in him as well.

Given his age (and the default presumption of heterosexuality), the proximal cause of his awakening is unsurprising: his first meeting with Ruth’s free-spirited, halter-topped, and ceaselessly witty roommate, Amber, who will explicitly become James-Michael’s guide to the dangers and attractions of Hell’s Kitchen, and implicitly the inspiration for the development of his sexual feelings. Issue 1 has a lot of heavy lifting to do, but it still finds time to highlight James-Michael’s interactions with the three important adult women in his life. First, his mother, who encourages him to see the next stage of his life as “exciting”: “…the people you’ll encounter….And human beings aren’t as dull as you seem to believe, James-Michael.” Of course, it turns out that she is speaking from the perspective of an external observer, since the car accident that kills her reveals that she is a robot.

James-Michael’s literal awakening from his coma introduces him to Ruth, who never manages to forget a real connection with him. As she tells Dr. Barrow, “…you know this trouble I’ve had lately…relating.” She cannot be natural with the boy: “I tried too hard, it’s true. I must’ve come off like Miss Lois on Romper Room./ So sweet, so cutesy-poo. But why? That’s not me!” Where her maternal approach fails, Amber’s natural ability to, as Ruth herself puts it, “relate,’ breaks down some of James-Michael’s barriers. She meets him without realizing that he’s the future roommate Ruth mentioned, and cracks wise about James-Michael’s chess match against himself. James-Michael’s response is more open than anything he has said to date: “It’s easier…when you feel like two people all the time, anyway.”

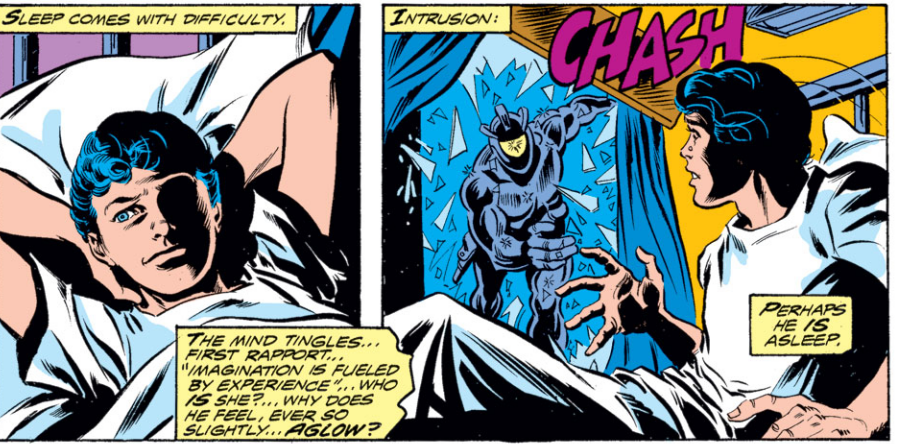

That night, right before the robot crashes into his hospital room, James-Michael can’t sleep. The description of his insomnia starts out with the same mind/body dichotomy highlighted in the first Omega monologue, but quickly settles on James-Michael as a self:

“The mind tingles…first rapport…”Imagination is fueled by experience.” [a quote from his father] ….who is she? Why does her feel…every so slightly…aglow?”

Whereupon his is attacked, and uses the strange energy from his hands to protect himself and Omega. Again, he experiences his own bodily sensations with detachment: “This rawness of nerves… is new to me…I’m not accustomed to pain. It interests me…” Given the sexual preoccupations that prevented him from sleeping, the comparison to masturbation practically writes itself. Instead of hairy palms, he gets omega-shaped stigmata.

Notes

[1] Omega the Unknown was the first Marvel comic to establish Hell’s Kitchen as the epicenter of Manhattan urban blight. Hell’s Kitchen was then ignored until Frank Miller made it the home of Daredevil in the 1980s. When Gerber and Skrenes were writing for Marvel, Hell’s Kitchen was a run-down, sketchy area; now it’s basically the theater district, but Marvel properties (in comics and on television) have kept Hell’s Kitchen suspended in 1970s amber as a kind of theme park of poverty and crime.

[2] The split also vaguely resembles Julian Jaynes theory of the bicameral mind.