Obligatory Comic Book Fight Scene

Roughly halfway through “Zen and the Art of Comic Book Writing,” the experiment with comics-as-person-essay Gerber wrote when he missed the deadline for Howard the Duck 16, Gerber and artist Tom Palmer include a two-page spread entitled “Obligatory Comic Book Fight Scene”:

There is one rule of comic book writing which simply cannot be violated, even by a writer in search of something as impalpable as his soul or Las Vegas.

Being a visual medium comics theoretically requires at least a modicum of action to engage and sustain reader interest.

Thus, in the interest of sustain your interest, we reluctantly present this BRAIN-BLASTING BATTLE SCENE, pitting an ostrich and a Las Vega chorus girls against the MIND-NUMBING MEANCE of a KILLER lampshade in a DUEL TO THE DEATH!!

Since we only get one picture for this CLASH OF TITANS, though, we’ll have to tell you the outcome. The ostrich sticks its head in a manhole, shrugging off all that’s happened and returning to his secret identity as a roadblock. The chorus girl finds herself in the thrill of battle, becomes one with her headers, and is elevated to goddess hood. The lampshade dies. Basically, it’s like every other comic mag.

Well, almost. The villain’s death is certainly a common trope. The chorus girl’s fate sounds like something out of Englehart (Mantis ascending, the Ancient One becoming “one with the universe). And the ostrich? Pure Gerber. Or, more to the point, pure Howard.[1] Howard desperately wants to be that ostrich.

This is not to say that, in addition to being trapped in a world he never made, Howard is stuck in the body of the wrong type of bird. Though no doubt a happy coincidence, the name for Howard’s species is also a command: duck!. Howard’s moral impulse is often to get involved, but his rational self usually reminds him that interference is futile. In Omega the Unknown, Gerber and Skrenes take advantage of the title character’s complete ignorance of Earth mores to show him repeatedly confused and hesitant about the conflicts in which he finds himself, but that hesitation disappears halfway through the ten-issue series once Omega begins to find a purpose. Howard's series lasted much longer, but his wavering never wavered.

As early as Issue 2, Howards contemplates leaving Beverly to her fate rather than go after the Space Turnip. In issue 4, he tries in vain not to concern himself with Paul Same’s bizarre, violent sleep disorder. He allows himself to be drafted as the All Night Party’s presidential candidate in Issue 7 because “I guess I got nothin’ planned between now and November.” And in Issue 9, he has no desire to figure out who tanked his campaign weeks before the election.

The manufactured scandal that doomed Howard’s candidacy (the publication of a faked photograph of him and Beverly taking a bath together) culminates in a story that makes his internal struggle with action and inaction the key to the next several months of stories, not to mention highlighting this conflict as one of his defining traits. A presidential election is the political equivalent of a super heroic “obligatory comic book fight scene,” except that Howard has no interest in the stakes:

“Aaah—what difference does it make? I mean, it’s not like I thirsted after the presidency!

I just wanted a project to occupy my time ’til November!”

The party’s leader gives him and Beverly airline tickets to Canada (the foreign power behind his downfall), telling Howard that he could come back “the conquering’ hero.” Howard will have none of it: “Over my dead body. / I’ve bled enough for this cause.” But Beverly is adamant, and Howard reluctantly assents.

The plot against Howard was real, but the motivations underlying it are impossible to take seriously. An old man in a wheelchair sitting on a porch under a huge sign identifying him as “Pierre Dentifris, Canada’s Only Super Patriot” was paralyzed when the US dropped a bomb on him during his attempt to dam the Niagara Falls with the help of one million beavers. He is aided by young American who blames ducks for his brother’s death in Vietnam. It’s a story of geopolitics, but played entirely as farce. And none of it means anything to Howard.

But Pierre, now wearing a beaver-shaped exoskeleton and calling himself “Le Beaver,” makes it personal when he kidnaps Beverly, traps her in a tree on the edge of the Niagara Falls, with a team of beavers slowing gnawing away at the trunk. Everything is set up for a fight to the death between Howard and Pierre, one that Canada’s only super patriot insists on seeing as allegorical (“Vous thought I was a helpless cripple—ze way all you Americans think of Canada itself!”), part of his master plan to have Canada annex the United States. It is also a parody of a classic superhero standoff—two animal-themed protagonists about to use their fists to determine the course of history. And, most important, it visually represents the narrative bind in which Howard has been trapped for the entire issue. “Here I go a’followin’ again—no doubt directly into the ear, nose, or throat of death./ My head is startin’ to ache.” Le Beaver is standing in the middle of a tightrope stretched from the Canadian side of the Falls to the American side, demanding that Howard join him in battle on the rope:

Howard: “Keep your hairshirt on, pal! I’m com—

“I’m c—

I’m—“

Howard (thinking): “The hell I am!”

Howard head back to the safety of cliff.

Le Beaver: “Coward!!! How dare vous turn back?!”

Howard: “Aah—Chew it, Pierre!

“I just figgered out what this headache was tryin’ to tell me!

“An’ as far as I’m concerned—you an yer politics—

“—can go jump!”

Le Beaver falls, Beverly congratulates him (“You were brilliant!”), but Howard merely exclaims “Feh!” and waddles away.

Howard’s rejection of Le Beaver’s challenge is consistent with his own worldview and jaded stand on politics: nationalism is pointless, as is solving conflicts with violence. But at the same time, he has violated one of the fundamental rules of the superhero genre by refusing to engage in the obligatory fight scene. Howard puts it best in the next issue: "There's really nothin' glamorous about gettin' killed to perpetuate their masculine stereotype." He has rejected the norms of masculine heroism (to the extent that he saves Beverly at all, it is by accident), and has proven himself an inadequate protagonist in his own superhero-adjacent book.

As Howard himself proclaims in issue 25, actions have consequences. So, too, does inaction. Howard’s shame over his non-performance at Niagara Falls causes a nervous breakdown that starts with an issue-long nightmare/fantasy sequence in issue 10, has him hearing voices in issue 11, and consigns him to a mental hospital from issues 12-14. Like the Man-Thing after his encounter with the tormentors of young Edmond, Howard has reached the limits of his emotional capacities.

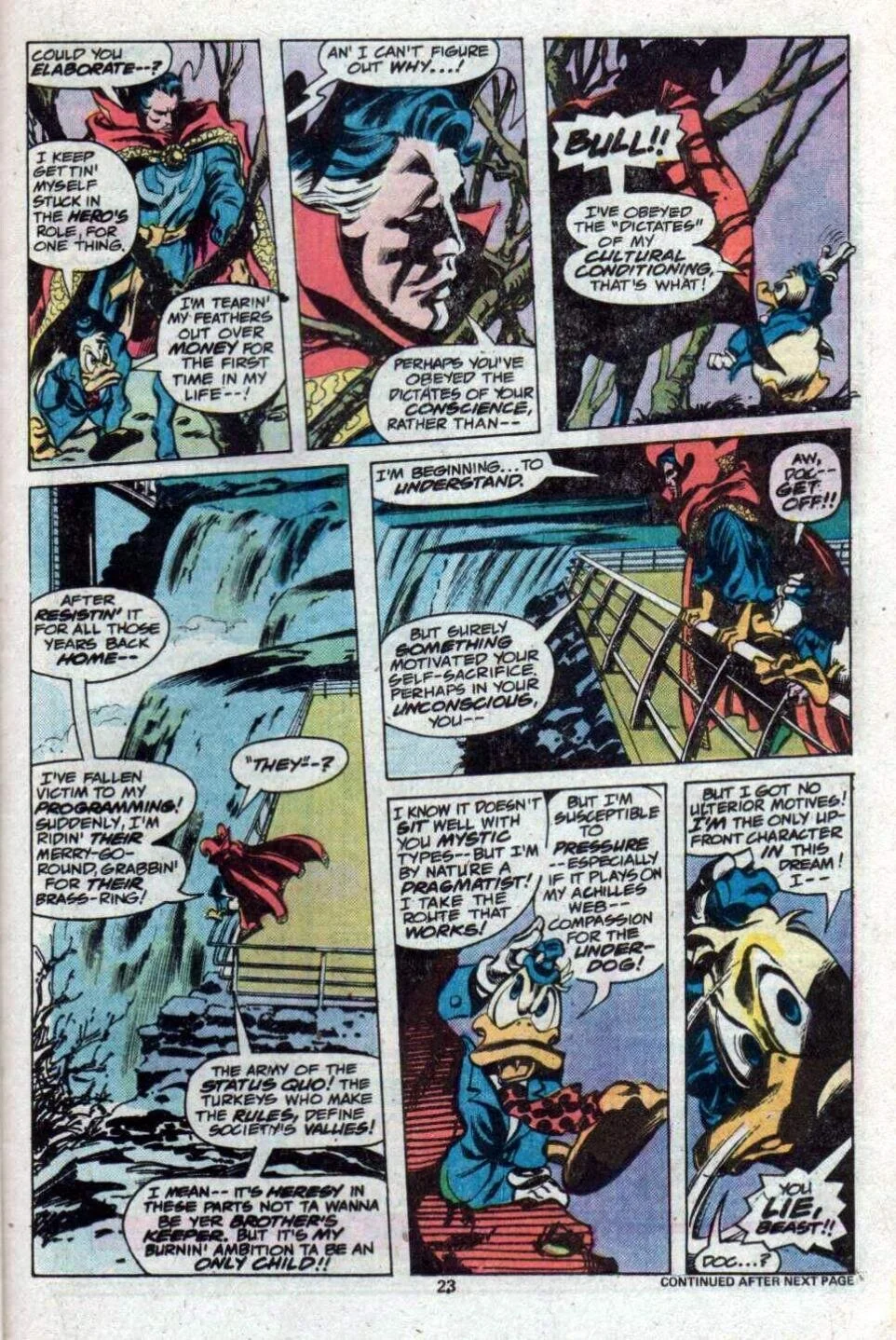

Issue 10 (“Swan-Song of the Living Dead Duck!) is most a portentious exploration of Howard’s psyche, until he last few pages, when he encounters a dream version of Dr. Strange calling himself “Dr. Piano.” Prompted to discuss his problem, Howard puts it plainly:

“Since I came to this idiot world, I’ve been behaving completely contrary to my true nature."

[….]

“I keep gettin’ stuck in the hero’s role, for one thing."

[….]

“I’ve obeyed the ‘dictates’ of my cultural conditioning, that’s what! […] I’ve fallen victim to my programming!”

[…]

“I mean—it’s heresy in these parts not ta wanna be yer brother’s keeper. But it’s my only ambition to be an only child!!!”

[…]

“…I’m by nature a pragmatist! I take the route that works!

“But I’m susceptible to pressure—especially if it plays on my Achilles web—compassion for the underdog!"

Inevitably, the dream leads him back to his confrontation with Le Beaver ("the only fight I'd ever walked out on--'cause it was just too ludicrous!") , Given the chance for a do-over, Howard, fights and, of course, loses: "I was brave. I was heroic. I acted in the best macho tradition of unthinking pugnacity an' I died...for honor." He had hoped that going against his own better judgement would at least heal his emotional trauma, but instead he imagines himself damned to hell for all eternity.

Howard can conceive of no scenario where he wins, because the logic of a Marvel comic will not provide him any. Howard's problem is, of course, Gerber's: perhaps he could have come up with a brilliant, but likely ridiculous, way in which a miniscule duck could beat a man in a giant, super-strong exoskeleton while balancing on a tightrope, but that was not what he needed the story to do.

Instead, Gerber uses Howard's (and occasionally, Beverly's) jaundiced view of the increasingly odd obstacle they encounter to keep the comic balanced between the genre's need for adventure and novelty and the book's apparent goal of sustaining an unrelenting sense of either not belonging or refusing to belong. Subsequent writers who have used Howard tend to make a fundamental mistake here, confusing Gerber's expression of a philosophical standpoint with mere genre parody. The point is not simply that mainstream comic book tropes are absurd, but rather that everything is.

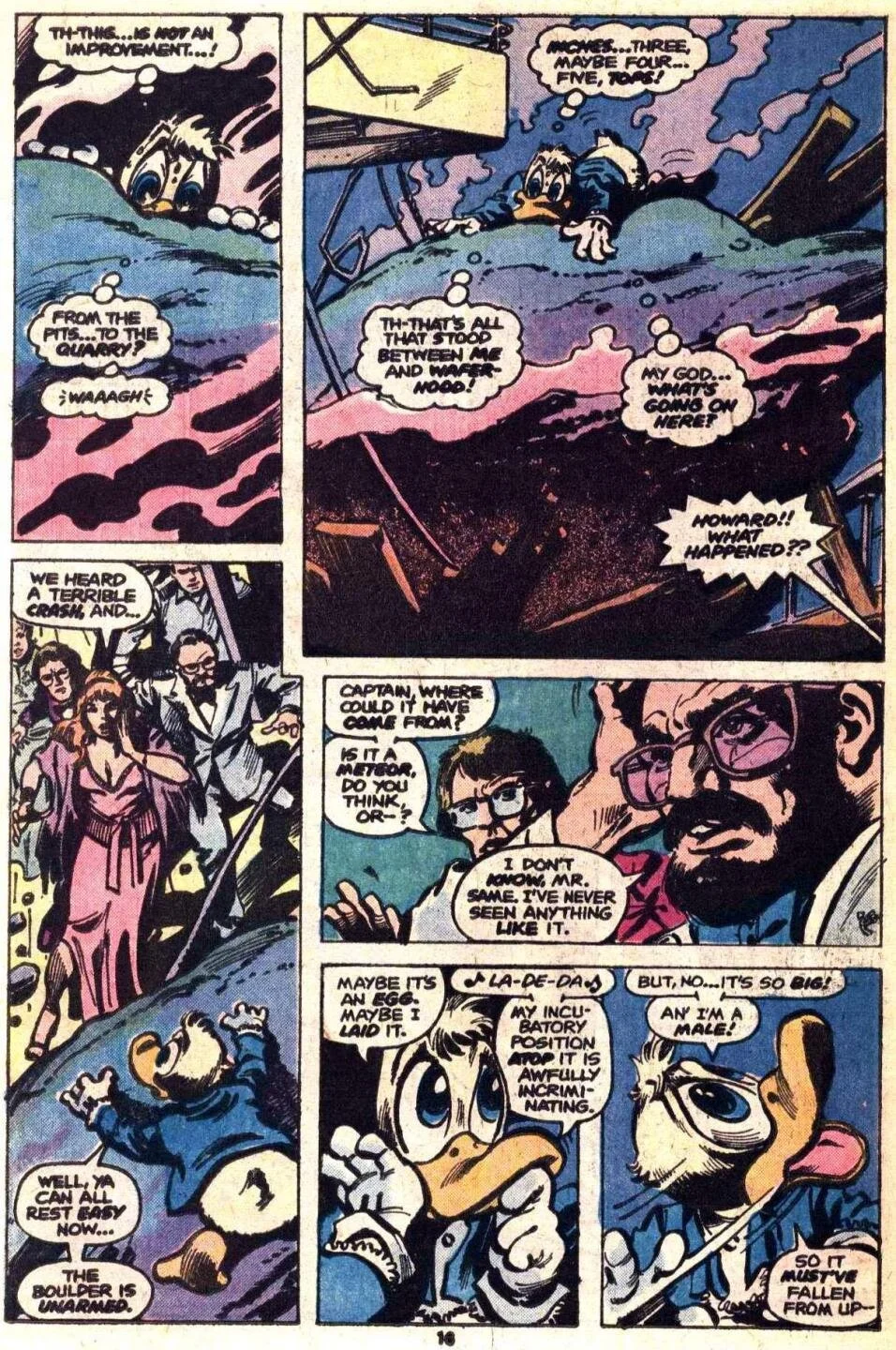

Thus even after Howard has recovered from his months of mental illness, his fundamental attitude does not change. Issue 15's "The Island of Dr. Bong" sees Howard, Beverly, Paul, and Winda taking a cruise on the "S.S. Damned," their attempts at relaxation foiled by the fact they are in a comic book that requires action and conflict. When Howard falls overboard and nearly drowns, he thinks, "I must be the very personification of the rage to live. / Hit me. Dunk me. Insult me--I'll still hang in there. / I wonder why--?" His near death when a chunk of granite drops form the sky onto the deck merely gives him another opportunity for sarcasm. The passengers and crew arrive just as he has crawled from the wreckage on top of the rock: "Maybe it's an egg. Maybe I laid it. / La-de-da/ My incubatory position atop it is awfully incriminating. / But no...it's so big!/ An' I'm a male!"

Howard the Duck functions best when it gives the title character ample opportunity to do what he does best: riff on the action as it unfolding. It is as though the wise-cracking robots of Mystery Science Theater 3000 were providing their commentary while actually stuck within the films that they are watching. The plots of a typical Howard comic are a tenuously connected series of events, united primarily by how the duck responds to them. In the case of "The Island of Dr. Bong," Howard is on the cruise ship precisely to avoid these sort of situations that send him on a sardonic spiral of commentary. On the very second page, her remarks that "in the event of nuclear disaster the entire free entrerprise system--/--could be preserved about this ship for future generations," before remembering that "I promised myself: no heavy thoughts this trip." It's a resolution that is impossible to keep, and not only because he is in a comic book. The cruise ship is just another version of the situation he's found himself in since his arrival in the Marvel Universe, if not before: from "trapped in a world he never made" to "trapped on a ship he cannot steer."

Yet events continue to conspire to get him off this very boat, from the shuffleboard puck that knocks him overboard to the stone swan that hatches out of the boulder that nearly crushed him (it turns out it was, indeed, an egg). Right before this final exit from the SS Damned, the four main characters (Paul, Bev, Howard and Winda) collectively riff on their latest plight (a rain of boulders that has all but destroyed the ship:

Paul: "All I can think about is Bob Dylan: 'Everybody must get stoned.'

"Somehow, I always figured the meant it this way."

Bev: "That's funny--so did I."

Winda: "Who's Bob Dywan?"

Howard: "I dunno....I just hope we're quoting survivors, not martyrs."

Winda: "How twue! Fwame of mind is so impor--"

Before she is cut off, Winda is making a salient point. For once, Howard, however, sarcastically, makes a quip that is a vague gesture towards optimism. Of course, any hopes are dashed when the boulder "hatches" a granite swan that spirits Bev and Howard away to a mysterious island, dumping them in a pool of quicksand. At this point, Howard the Duck starts to look like Pilgrim's Progress: the allegory is all too clear. Twice now Howard has been knocked overboard from the ship to which he has tentatively surrendered his control, first in the shuffleboard incident, and now with the swan. Moreover, try as Howard may to improve his outlook and make his peace with his surroundings, the ship has hardly been congenial; the only reason he was on the deck when the boulder dropped was that he had raced from the dining hall after being served duck l'orange ("casual cannibalism,” as he called it). Howard and Bev were trying to take a break from their nonsensical adventures, but if there's one thing the Howard the Duck comic is not, it is escapist. The granite swan drops them in a bog. Now the pair are literally mired in quicksand, mere moments away from death by suffocation. All in all, an apt metaphor for Howard's usual plight.

This being an ongoing comic, they are, of course, rescued, but the form of their deliverance (monstrous, gargoyle-like creatures) is so appalling that Howard rejects the offer of help: "Uhm...no thanks. I'll pass./ [...] / Honest--no offense! It's just...if you guys are any indication of what's comin'--/ --I'd prefer to bow out now." Recovered from his nervous breakdown, he is back in the same situation in which his series began: contemplating a voluntary death by drowning. All he sees in his future is more of what he has encountered in the past, and he wants no part of it.

Fitting, then, that what changes his mind is a grotesque version of himself: a giant, humanoid duck extending a flipper: "Don't be foolish, brother. Take my hand." Finally, it is Howard's turn to exclaim, "Y-you're a duck!" The explanation will involve mad science, but the point is still taken: the only one who can save Howard is himself.

It is at this point, the last page of "The Island of Dr. Bong," that Beverly becomes the voice of disappointed exhaustion rather than Howard. Beverly is a difficult character to pin down. She's often drawn for sex appeal (though not nearly as much as she would be after Gerber's departure and the comic's replacement with a magazine for "mature readers"); her most obvious narrative function is to give Howard someone to talk to (although the nervous breakdown sequence shows that Howard can function as his own interlocutor should the need arise); she is not infrequently put in the role of "damsel in distress"; and, finally, her generally cheery and supportive outlook make it is easy to dismiss her as simply playing the "nice girl" in contrast to the curmudgeonly Howard.[2] But Beverly is not a bimbo. She can hold her own with (or against) Howard on the level that really matters for the duck (and, presumably, his creator): the level of language. She does not simply agree with everything he says, or, even worse, fail to understand him. Though less caustic, she is as verbally quick as Howard.

So it is completely consistent for Beverly to say, after being rescued from quicksand by strange animal/human hybrids, "I know I should be reacting more--what? Visibly to this madness but--"

Howard: "Don't apologize, toots--I've been there.

"After a while, it's all ya can do to fake the expected gasps and moans of--"

Dr. Bong: "Surprise!"

Beverly: "Oh jeez, now wha--?

"OH MY GOSH!!"

Dr. Bong: "Why--how charmingly inarticulate! Thank you, Ms. Switzler.

"And may I welcome you to the island of --

"Dr. Bong!"

Howard: "waaugh"

Beverly: "Uh...what if I said, 'No, you many not?"

Dr. Bong calls Beverly "inarticulate," which would not normally be accurate, and also fits in with his need to see Beverly as an object rather than someone with a mind of her own. But at the moment, he is also correct: the absurdity of seeing a caped-clad man with a golden bell-shaped helmet and a matching orb instead of his left hand has temporarily rendered both Beverly and Howard speechless. After everything that the two have been through, including their increasing detachment from the perilous events that befall them, wordless shock is not just appropriate; it is, in its way, a step forward. Howard the Duck has replaced the obligatory fight scene with the mandatory absurd tableau.

Notes

[1] Many years later, Gerber would adapt the premise of these two pages for a 6-issue Vertigo miniseries called Nevada.

[2] Given the development of the series from Issue 15 onward, it looks as though Gerber felt he was running out of things to do with her. She and Howard would separate when Beverly agrees to marry Dr. Bong to spare Howard's life in issue 18, reunited only after Bill Mantlo took over the book (Issue 31). Howard feels her absence keenly, but Gerber supplies a series of new foils for Howard over the next year. In his last issues, Gerber gives Beverly's story an unsavory turn. After supplying Dr. Bong with a backstory that functions as an incisive critique of masculine entitlement (Dr. Bong is basically in an Incel before his time), Gerber shows Beverly increasingly frustrated that Lester (Dr. Bong) is not paying attention to her; she demands that he "play house" (Issue 25). Osvaldo Oyola's critique of this misogynist turn is particularly apt (https://themiddlespaces.com/2020/05/12/waugh-and-on-and-on-5/)